NOAA funded marine scientist uses OSPool access to high throughput computing to explode her boundaries of research

June 13, 2024Dr. Carrie Wall, a research scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder, shares how access to OSPool resources has allowed her team to expand the scope of their research and to fail, unconstrained by the cost of computing in the cloud and the associated restraints that places on research.

A marine scientist faced the daunting challenge of processing sonar data from 65 research cruises spanning 20 years, totaling over 100,000 files. The researcher, Dr. Carrie Wall, braced herself for a grueling 30-week endeavor of single stream, desktop-based processing. However, good fortune intervened at a National Discovery Cloud for Climate (NDC-C) conference in January 2024 when she crossed paths with Brian Bockelman, the principal investigator (PI) of the Pelican Project and a Co-PI of the PATh Project.

Wall discussed with Bockelman the challenges of converting decades’ worth of sonar datasets into a format suitable for AI analysis —a crucial step for her NSF-funded project through the NDC-C. This initiative aimed to develop the cyberinfrastructure essential for implementing scalable self-supervised machine learning on the extensive water column sonar data accumulated over the years.“We all went around and did five-minute presentations explaining ‘here’s what I do, here’s what I work on,’ almost like speed dating,” recounted Bockelman. “Listening to her talk, it was like, ‘this is a great high throughput computing example.’” Recognizing the volume of Wall’s project, Bockelman introduced her to the OSPool, a shared computing resource freely available to researchers affiliated with US academic institutions. He observed that Wall’s computing style aligned seamlessly with OSPool’s capabilities and would address Wall’s sonar processing bottleneck.

With Bockelman’s encouragement, Wall and her team’s software developer, Rudy Klucik, easily created accounts and began modifying their computing workflow for high throughput computing.”The process was super easy and very accommodating. Rachel Lombardi, a Research Computing Facilitator for the Center for High Throughput Computing, walked me through all the details, answered my technical questions, and was very welcoming. It was a really nice onboarding,” enthused Klucik. What followed was nothing short of a paradigm shift.

Within the walls of the University of Colorado Boulder lies CIRES: The Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, a partnership between the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the university itself. CIRES employs a workforce of over 800 scientists and staff, actively involved in various aspects of NOAA’s mission-critical endeavors. Among them are Wall and Klucik, both members of NOAA’s team. NOAA’s mission centers on supporting healthy oceans. Dr. Wall has dedicated the past 11 years to leading the development of national archives for water column sonar data, a task undertaken through the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), NOAA’s archival arm.

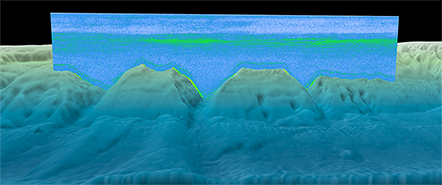

Wall and her team have archived over 280TB of water column sonar data at NCEI, which serves not only NOAA’s scientists but also other agencies and academic institutions. However, there was a significant issue: it existed solely in its native, proprietary, and exceedingly complex industry format. Despite being hosted on Amazon Web Services (AWS) for accessibility, as Wall explained, “a lot of expert knowledge is needed to even open and read these files.”

“NOAA scientists, mostly from the National Marine Fisheries Service (NOAA Fisheries), have collected in all U.S. waters - from the Arctic Ocean to the Caribbean and off the entire U.S. coastline. In just the Gulf of Maine alone, NOAA Fisheries scientists have collected over 20 years of data going back to 1998. All of these data have been archived so not only do we have a very large volume of data, but also a very long time series covering critical habitats,” Wall explained. “The majority of these fascinating data have been used to support fishery stock assessments,” Wall emphasized. “There’s a lot of these data, and in collaboration with experts we want to find out more about them.”

With the help of the OSPool, Klucik has been able to successfully develop a workflow that he now executes smoothly. This involves reading files from an AWS bucket, processing and converting them into a cloud native Zarr format, and then writing that data out to a publicly accessible bucket, available under the NOAA Open Data Dissemination program. Wall added, “This will now serve as our input for the AI model.”

Before discovering the OSPool, the original plan was to “fully utilize a cloud native processing pipeline, mainly composed of AWS Lambdas to do all our data conversion” described Klucik. “One common misconception is that cloud computing is cheaper than traditional computing, if the technical elements are all aligned properly it can be cheap, but in a lot of situations it’s still extremely expensive; in the back of our minds we were afraid that it might even be cost prohibitive to process the archive as a whole.”

However, it is important to acknowledge that before being set up with the OSPool, there was a bit of a learning curve. “I was completely new to high throughput computing infrastructure and didn’t understand how the processing worked,” recalled Klucik. “So, a lot of my initial time was spent running ‘hello world’ examples to better understand the functionality. I started with one job, then scaled up to 100 and eventually 1,000 to get the concurrency we were looking to achieve. It involved a lot of trial and error to get everything right. It took about a month before I finally managed to run the full catalog of data properly.” Klucik noted that he was aware of the available resources, saying, “The OSPool documentation served as an invaluable resource for getting me oriented in a new computing environment.”

Although initially tasked with processing 100,000 files, their workflow using the OSPool has since surged beyond 400,000 files—an accomplishment that would have been financially daunting in a traditional cloud environment. Wall emphasized that “what OSPool has allowed us to do is fail, which is really, really good. Before [using the] OSPool, we started by processing a couple of cruises with a very small number of files in the cloud to be cost-effective; we didn’t want to make costly mistakes. Being able to use OSPool to iterate and strengthen our process, allowed us to then scale to the volume of data and number of files that we need to process. I don’t know where we would be without OSPool but it would’ve cost us tens of thousands of dollars. We didn’t have to sacrifice for a lesser workflow, one that we didn’t improve upon because it would have cost us more money. I’m really excited about where OSPool has allowed us to go, and now we can take that next step to say ‘okay, we have our foundation, which is our data and a great format, and we can build our models and additional workflows.’”

Wall’s testimony underscores OSPool’s role not just as computing capacity but as a catalyst for innovation, enabling teams to push boundaries and realize their full potential in research and model development.